God, be merciful to us sinners. Amen.

Writing 1,000 years ago, the Archbishop of Canterbury wrote, “you have not considered the weightiness of sin.” As we heard in Psalm 65, “Our sins are stronger than we are.” Other translations put it as “My deeds of mischief are too much for me” and “We are overwhelmed with our inequity.” Sin is one of those words that can often conjure up images of a wrathful god, inducing fear, guilt, and shame. And though we have a Confession each week in worship, and pray daily “forgive us our trespasses,” it does not mean that we have considered fully the weight of sin. Certainly, some traditions overly focus on sin, which is not what I am advocating for. But as someone who swings kettlebells six days a week, I can tell you that we can get into a whole lot of trouble if we don’t know how heavy the weight we’re working with is.

There

are at least a few reasons why we no longer consider the weight of sin. For

one, we live in a demystified world. “Sin” just isn’t a category that we are

trained to use. GDP, inflation rates, calories, positive test rates, polling

numbers, touchdowns – these are the categories of modern society. Ideas like

sin and atonement are no longer a part of our vernacular. So when the Church

talks about sin, we simply don’t have a bucket to put those sorts of ideas into.

Another

reason we do not consider the weight of sin is that some Christian traditions use

that weight to bludgeon people, and perhaps you’ve been stuck with that weapon

before. When sin is painted as the most important issue in faith, and it is not

the most important issue, then those who control the mechanisms of forgiveness

become powerful. This is what the Reformation was all about – and, ironically,

the denominations today that would identify themselves most closely with the ideas

of the Reformation are the same ones who perpetuate the theologies that led to it.

Because we have seen the damage that an unhealthy focus on sin can do, we shy

away from it.

Perhaps

the deepest reason though that we avoid considering sin is that we have been

trained to always be on top of our game, independent, and fully in control of

our lives. Sin is an affront to the idol of self-sufficiency. There’s a story

that one day Winnie the Pooh was in Rabbit’s home, and as bears often do when

they see a pot of honey, Pooh consumed it all. When it became time for Pooh to

go home for the evening, he starts to grumble. Rabbit asks, “What the matter,

Pooh?” To which Pooh replies, “The trouble is, Rabbit, your doorway is too small.”

Rabbit responds, “The trouble is, Pooh, you’ve eaten too much.”

Considering the weight of

sin means considering things about ourselves that we do not want to be true. As

one theologian has put it, “The world and the church that has become like the

world, will try to kill the messenger when it comes to sin, just like it did to

Jesus. First, the message of sin is indiscriminately inclusive: all have sinned;

second, it is narrowly exclusive: only Christ can solve the issue.” But just

because we don’t like the idea of sin, that does not impact the reality of sin.

Just as those who believe that Earth is only 6,000 years old have no impact on

the fact that Earth is about 4.5 billion years old.

I realize I’ve been

throwing that word “sin” around without really defining it. As we know from the

letter to the Hebrews, sin clings closely to us. Sin is not less than our wrongs

and mistakes, but it is also much more than that. That is the weightiness of

sin. Sin is something that we are captive to -something like gravity that pulls

us down, and only Jesus can give us the necessary escape velocity to break its

hold on us. Sin is not something that we can overcome by trying harder. Sin is

a way of describing the brokenness of our world – war, greed, selfishness, and

racism are all words that describe particular instances of sin. Sin is when we

are closed off and dead to the transforming and reconciling love of God. Sin,

as the Confession teaches us, can be things done or left undone; sin can be

about thoughts, words, and deeds; sins can be things we do as well as systems

that we are caught up in and benefit from. It is because sin encompasses so

much that it is so weighty – it has an enormous pull on us.

However, sin does not

erase the goodness and love out of which we are made. Sin is not the first

thing that God sees when looking at us, nor is it the last. Sin does not erase

the image of God that humanity is created in. Sin distorts the image. Sin is a

crack in the mirror, a smudge on the reflection. The inability to name sin is to

accept those distortions as normal and acceptable – so to downplay sin is about

as safe as downplaying the dangers of nuclear waste.

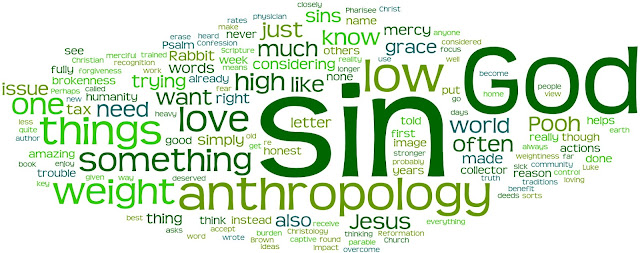

What a healthy respect

for the weight of sin leads to is what one author calls a “low anthropology” in

a recently published book. Anthropology, in this sense, isn’t about studying

cultures, it is a shorthand for saying “what we think of humanity.” So, a low

anthropology is one that has, well, a low view. And this isn’t about self-deprecation

or thinking the glass is half-empty, it’s just paying attention to Scripture.

In Genesis, we are told that humanity is made from the dirt of the earth; and

this is not a curse, but rather a blessing of being formed of the Creation

which God has called “good.” But the ground is low.

And thinking of ourselves

properly, as sinners, is quite liberating because a low anthropology means that

we shouldn’t expect perfection from ourselves, or anyone else. It helps us to

be freed from the tyranny of expectation. Author and sociologist Brené Brown

has said that vulnerability is the birthplace of love. Only when we are honest about

sin can we receive fully the love of God. Because if we pretend that we have deserved

love by our actions, we will constantly fear that we can lose that love, or

that we never really deserved it and feel like a fraud. Instead, God’s love is

a gift best described as grace – the surprising and unearned love of God which

can never be lost because it was never earned.

In this book, there are

three aspects to a low anthropology that are helpful in understanding the weight

of sin. The first is a recognition that we are limited creatures. None of us knows

everything, none of us does everything, none of us are immortal. One theologian

has remarked that sin is the only independently verifiable Christian doctrine. Any

honest look at the world will make it quite clear that things are broken, and

this brokenness is called sin. If we reject our limited nature then we have to

carry the crushing burden of always getting it right, something none of us can

do.

A low anthropology is also

about doubleness – which is best described by St. Paul in Romans 7: “I do not

understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing

I hate… I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good

I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do.” In other words, for the most

part, we all know what sorts of things we should be doing, the problem is not that

we don’t know that we should eat more vegetables, and read Scripture more

often, and volunteer in the community more instead of scrolling so much on our

phones, the issue is that we just don’t want to do those things even if we know

that we should want to. As this week’s Collect prays, we need God’s help in

loving what is commanded, because though we are all sheep in the fold of the

Good Shepherd, we often prefer to go our own way.

So instead of beating ourselves,

and others, up for being hypocrites, we can recognize that as our doubleness is something

we all contend with. The novelist Zadie Smith has said, “the hardest thing for

anyone to accept is that other people are real as you are.” It’s so easy to spot

the shortcomings in others while giving ourselves the benefit of the doubt, but

a low anthropology helps to know that we all struggle with doubled and competing

motivations.

A low anthropology also

names, and therefore helps us to confront, our self-centeredness. Back in the

days of typewriters, a typewriter repairman reported that the key that most

often needed to be replaced is the “I” key; not because the letter I is used

more often than any other letter, but because it tends to be struck with more

force than any other letter. It’s simply a linguistic accident that the center

of the word sin is “I,” but there it is. We were made for each other, made for

beloved community, but sin drives us inward and corrupts our view of the image of God found

in others.

So why do we talk about

sin, why name this low anthropology? Well, as Jesus said, “the truth shall make

us free.” If we cannot admit that we are sick, we’re probably going to think

there’s no need to see a physician and we’ll likely reject the medicine. Psalm

65 says that our sins are stronger than we are, yes, but it also says that God

will blot those sins out.

CS Lewis said that fallen

humans are not simply imperfect creatures who need a bit of improvement, we are

rebels who must lay down our arms. If we think of sin as only a minor issue, or

something that we can overcome with a few minutes of mindfulness each morning

then we will continue fighting for the side that is opposed to the love of God.

Admitting that we are captive to sin creates space in our hearts, our imaginations,

and our actions for God to do something new. But denying sin closes us off to

God’s amazing grace. It is as Jesus says, “only those who are sick are in need

of a physician.”

The reason why considering

the weight of sin is such a good thing to do is that it allows us to consider the amazing and beautiful grace of God in making all things new. As another Psalm,

the 103rd, puts it “For as the heavens are high above the earth, so

is God’s mercy great upon those who fear him. As far as the east is from the

west, so far has God removed our sins from us.” Episcopal priest and author

Barbara Brown Taylor wrote that “Sin is our only hope because the recognition

that something is wrong is the first step in having things set right. There is

no repair if brokenness is not acknowledged, there is no transformation in a world

that accepts wickedness as inevitable.”

If we have a low anthropology,

it is met by a high Christology – that is, a high view of what Jesus has done

for us. But a high anthropology has less room for Christ. We heard the prophet

Joel speak of God’s Spirit that will be poured out on all flesh – but if we

insist that we’ve got a decent handle on things, why would we need outside help?

And where we really see the contrast between a high and low anthropology is in

the parable told in Luke. The repugnant tax collector asks God for mercy, and

we are told that he receives it.

A high anthropology version

of this parable would list all the things that the tax collector did to earn

his forgiveness. Perhaps he would promise to do all the things the Pharisee

boasts of. Maybe Luke would have included a description of how the tax

collector changed his ways and found a different line of work. But the Gospel

is one of low anthropology and a high Christology, it is a Gospel that takes

seriously the weight of sin and the glorious reconciliation of God. The tax

collector tells the truth – he is a sinner in need of God’s mercy, and God’s

mercy is what is given by a gracious and loving God. Was the Pharisee also

justified? Probably because God’s grace is for everyone. But he probably wasn’t

able to enjoy his salvation because he was blind to God’s amazing grace.

The Church is a place to

be honest, a confessional where we name the reality of Sin. In recognizing our limits,

our inconsistencies, our egotism, we find the depths of God’s love that does

not depend on our worthiness, our deservingness, or our hard work. And just

imagine how much sweeter life might be if instead of trying to fight for something

that has already been given to us, we could simply enjoy that which we already have.

Jesus is the one to whom we can come when we are carrying the heavy burden of

sin and receive rest from trying to get it right, trying to be perfect, trying to

justify ourselves, because he has already done all of that for us.

God, be merciful me, a

sinner.